It’s been a little more than three years since my dad died unexpectedly on an otherwise uneventful Sunday afternoon, making me a fatherless daughter at age 27. It happened exactly a month before my 28th birthday, and a little under a month before his 61st.

My dad was my birthday twin. He was born in 1960’s Jamaica on the 10th day of April (64 years ago, today). Decades later, I was born on the 13th of the same month, becoming the only child of his to share an astrological sign with him.

“Wi both born April!”, he would often exclaim.

It’s around noon and I’ve just laid out my yoga mat. My phone is on silent, but before I start my yoga session, I see it light up. My younger brother. Hmm, he doesn’t usually call me. He’s 13 and is really into gaming. He does not have much time for phone calls with his big sister, who is twice his age. I get it.

I hear tears in his voice as he tells me that something is wrong with Dad. Yes, he has experienced minor health issues before, but “not to this extent.” They’re taking him to a local hospital, my brother tells me. I head there.

As I am walking up to the hospital, a stranger asks me a question to which I do not know the answer. In response, I tell her just that—I do not know. I don’t care to find the answer either, because there is something wrong with my dad. I hear the sound of kissed teeth behind me.

I look back slightly and sardonically scoff to myself, thinking that there is something wrong with my dad, and here is this stranger, pissed at me—another stranger—for not knowing the answer to their stupid question. They say to always be kind to others because you never know what someone is going through, and I’m reminded that cliches are cliches for good reason, and their universal truthfulness often and ironically escapes us.

“We think of clichés as boring and predicable, but they are actually one of the most dangerous things in the world. Your brain can’t engage a cliché, not properly—it skitters right over the phrase or sentence or idea without a second thought.”

In the Dream House, by Carmen Maria Machado

I knew at an early age that I’d never be “daddy’s little girl,” and quite frankly, I can’t recall a time when I genuinely wanted to be. At some early point, my underdeveloped mind as a child subconsciously concluded that there was no use yearning for something that was out of my reach. Daddy had a lot of little girls and besides, I was safe and comfortable at home with my mother, who had never been rumored to spank children, like my father had been.

I was instead mommy’s little girl, who spent all of her waking hours soaking up the warmth, love, and care that my mother let flow and cover me like a Jamaican sun ray. When I wasn’t with my mother, I was thinking of her, yearning to be back in the castle that she built out of our Bronx apartment.

I cried and cried when I had to leave my mother to start pre-K. Why? I didn’t understand. To me, the start of school meant leaving the comfort of my mother’s home and arms to sit around learning new words with strangers. I eventually adjusted and even excelled, but I remain attached to my mom to this day and still hate to leave her.

For the first few years of my childhood, I refused to hang out with my dad outside of my mother or grandmother’s home until one day, he sat me down and explained to me that he only spanked the children of his who misbehave. It’d be safe for me, I reasoned with myself. I am a pretty good kid.

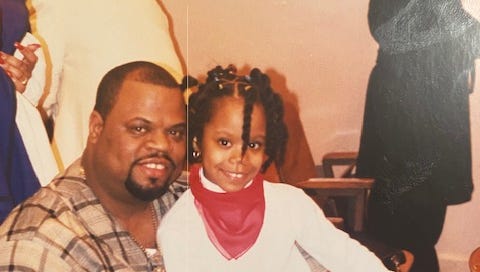

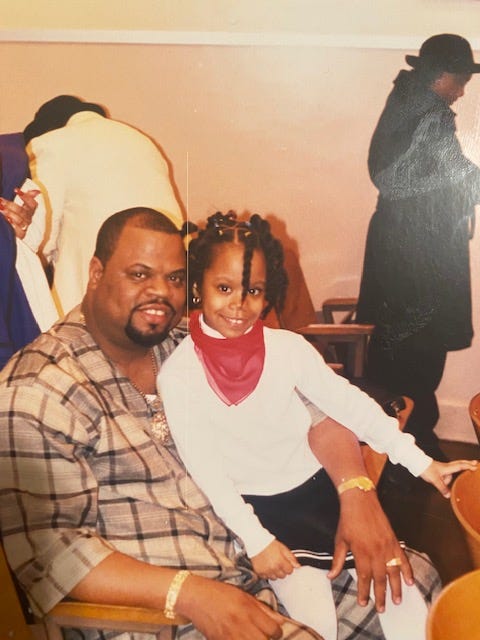

And so began our father-daughter hangouts—which never really included just us for more than a short time—that would create within me years’ worth of mundane, happy, exciting, and painful memories.

I never met my paternal grandparents because they died decades before I was a mere thought swirling around the minds of my loved ones— before my physical existence on the earth came to be. It wasn’t until my dad’s sudden death in 2022 that I began to understand what my having never met my paternal grandparents meant for my father more deeply and clearly.

Weeks after my dad’s death, I was on the phone with his cousin, who was also one of his best friends. He shared that when my dad would get sad about having lost both of his parents as a teenager, just six or so months apart, he would sing the lyrics to a song called Nobody’s Child.

I'm nobody's child

I'm nobody's child

Just like the flowers

I'm growing wild

No mummy's kisses

And no daddy's smile

Nobody wants me

I'm nobody's child

How lost and devastated the teenage version of my father must have felt, having lost his two anchors in this life before the age of 18, and with barely any time in between. And how lonely. I cried the first time I listened to that song—feeling sorry for my now fatherless self and even sorrier for the parentless teenager that was my dad. Rejected by their remaining immediate family, my dad and his two brothers were left to fend for themselves in Jamaica, sometimes not having enough food to eat.

So as a teen, my dad ate dejection, poverty, and grief for breakfast when there wasn’t anything else for which to reach in the cabinets.

When my dad’s last brother died roughly twenty years ago, he came quite undone, and I genuinely didn’t recognize him in the following months. My dad, 6’1” with a baritone voice and larger than life, had turned into a shell of himself. I remember walking past his room after one of the funeral services. He looked up at me and his face was wet, eyes red and puffy. The grief over the loss of the last member of the immediate family with whom he grew up even changed his voice for a while. It was suddenly soft and my dad was not a soft-spoken person.

When he was a poor and parentless child in Jamaica, at least he had his brothers. It was the three of them tied together by blood, love, and struggle, and I imagine that they clung even closer together during those years after losing their parents 6 months apart, raising themselves.

Raising each other.

Now he didn’t even have them anymore, and my father’s sadness was palpable, even to my 9-year-old self.

Years later, when I asked him how he copes with life and loss, he told me a story about him driving on the highway sometime after his last brother died. He said he was driving and crying again because he was nobody’s child, and now he was nobody’s brother, and, and, and.

Right then, he was just about to experience his own death by asphyxiation at the hands of not another human, but of his grief. Right then, when his sadness swallowed him whole like the whale did Jonah, my dad yelled, “Uncle!,” because he didn’t want to be disappeared by his grief—stuck in a whirlpool of raw and ugly emotions that kept pushing him back down as he fought and flailed, desperate to find an exit.

And so my father’s grief became merciful because it could see that he was trying, trying so hard to live again, and he was spat back out to land, as Jonah had been.

Right then, my father had a welcomed shift in perspective.

“Him gone! Him dead. He’s not coming back. The nigga is dead.” He said he shouted to himself, alone in his car, fresh tears still clinging to his face.

“And from then, mi neva cry again.”

I’m at my dad’s wake and a slideshow of his lifelong memories is playing. I watch and begin to notice that the slideshow has restarted and I still haven’t seen any of the numerous photos of my father and me that I sent in for their display.

“She’s your sister by blood, but not in spirit.” A beloved family member once said to me.

As punishment for years of avoiding her toxicity, for protecting myself by not being around my dad or his side of the family much, for financially contributing to, but not begging on my hands and knees to be a part of the funeral planning process in which my help (besides the financial kind, of course) was unwanted, for not falling into a life of toxicity and mediocrity (like her), and for not canceling an already planned trip to my father’s birthplace of Jamaica (which aided my healing process instead of destroying it, like staying home and fighting to be a part of something I was never going to be a part of in the first place would have done), I was excluded from a slideshow that was supposed to represent my father’s life over the years—from a slideshow that I and everyone else in the family know that he would have wanted me in.

But alas… I cut my losses, basked in the pride I felt that my teenaged self had the foresight to cut a scum of the earth person who would do something like that to someone out of my life many years ago, remembered that my Dad, unfortunately, acted as an enabler of this venom when he was alive, and let what little love I may have had left for her in my heart turn into dust as the remains of our father would eventually become.

Meanwhile, on that trip to Jamaica for which I was being silently judged by some of my family(?) for not canceling, I spoke to my father in the ocean and treaded water for more than a few seconds for the first time. I cried and laughed and danced and was happy that I wasn’t back home in the Bronx, sending conciliatory pleas to be a part of my own dad’s funeral to a person of whom I made a living ghost in my life long, long ago.

The night after the wake, I was walking with one of my sisters who is my sister in blood and in spirit, and one of my younger brothers was walking behind us. I was beginning to drown myself in unwarranted guilt. Dad was dead and I spent a lot of time avoiding him in my early adulthood. “I stayed away for so long.”, I lamented aloud, to no one in particular, barely even expecting a response.

“To heal.” I heard my brother say.

I loved him so much at that moment and was speechless. My brother saw me, and he understood, having experienced worse from our dad.

He was always harder on his boys.

How refreshing it is to be understood in a sea of misunderstanding and judgment. How heart-warming to have a loved one stand in the way of an oncoming spiral—morphing into a rock on which to hold on, just when the waves threaten to overpower you and drag you into the dark and lonely crevices of your mind.

I set my guilt down at the side of the road and watched it evaporate before me as I stepped into the passenger side of our sister’s car.

Following my uncle’s death, my dad eventually got his voice back, and yes, of course, he was still sad, but for the most part, it was soon back to regularly scheduled programming of my childhood experience of his personhood, made up of a confusing mixture of honey and venom.

At times, I thought that because I knew who my father was at an early age, his fingernails that moonlighted as claws when he was angry couldn’t puncture my heart after a while.

I was wrong, and sometimes the venom remained inside of my pores for as long as I wished the honey would. For a long time, I resented the fact that what my father did or didn’t do hurt my feelings, even though I understood what caused it, and even though I had spent years designing protective armor for myself.

What a crushing blow it is to realize that it still takes but one funny look or a raised voice from your dad to turn your shiny, tin armor that was years in the making into paper mache—your inanimate protective gear falling on the ground in slow motion and landing in the shape of something like The Joker’s smile, mocking you.

In those moments, I was 5 years old again, panicking, terrified of looking stupid, and trying to figure out what it was that my dad wanted little me to do.

I make it to the hospital room and I can tell that my dad is likely already dead because his limbs look flaccid and his skin pale.

Several doctors were still trying to revive him until it seemed the collective agreed and realized that there was no use anymore, and left the room. The remaining and presumably supervising doctor asked me if I’d like to say anything to my father, even though he was already dead, and I could only think to say “I love you.” two or three times.

After stepping outside of the room so that I could let other family members have some time with my dad’s dead body, I must have looked dazed, or as if I were unsteady on my feet or something, because someone at the hospital (likely a nurse) rushed to grab me a chair.

Hospitals are such sad places.

There was this other young woman there, wheeling who I think was her mother around, teary.

Looking back, it felt like a reality show competition.

Do you know how on America’s Next Top Model, Tyra Banks used to stand in front of the last two contestants with only one picture that she would hold facing her? We knew that whoever was not in the photo when she turned it around was going home and lost the competition. Being at the hospital the minutes before I found out my dad was dead felt like that. Who is losing a family member today? Turns out, it was me. I was the one going home with a loss.

Reminiscing on that fateful hospital visit, I think of Save the Last Dance, when Sara learns that her mother has suddenly died in a car accident. She is about to fall to the floor, but she is held up by the people around her. I’ve seen that movie a million times and that’s one scene that always stood out in my head. It’s interesting to me that sometimes we get news so disturbing that our knees start to give out.

Our minds tell our bodies, “Oh no! Something is wrong! This is… too much! We… are going down.”

Ironically, humans becoming unsteady on our feet after learning of a tragedy is still a sign of life—our tears stinging harbingers of a future, whatever that may look like.

A good memory I have of my dad, which I didn’t know then would be one of the last of him in this life, is when I got back from England in 2021, after spending a year abroad obtaining my master’s.

He saw me first—before any of my other family members saw me, and before I saw him. I remember him calling out my childhood pet name that he had granted me over two decades ago before I could even talk, and I skipped into his arms—unhindered by any past hurts. Light as a feather, I was, and I could feel the sun even though we were inside a stuffy airport.

After nearly a year away from home, I was so happy to see family, a familiar face—his face, that I naturally and subconsciously buried all of my disappointments and resentments deep into my toes, then. What floated to the surface was nothing but genuine love. It’s a good thing, too, because that was the last bear hug that I received from my father.

That year would be his last full one with us on earth.

After some months of being back home, the same old disappointments and resentments fought their way up from my toes and right back into my heart, as they do.

Hello, darkness, my old friend.

And I began to quietly isolate myself from Dad again.

I’d answer all of his calls and maybe even call him first sometimes, but I didn’t visit him much upon my return. He never really visited me either, though, and he stopped picking my sisters and me up as children, the minute he realized we were old enough to get to his home on our own.

The last question my father asked me when he was alive, a week before his passing, was, “When yuh coming to the house?”

The next time I would visit his house, it would be on my way back from the hospital, and the only one missing would be him.

There were a bunch of people at my Dad’s house on the day that he died. His home looked like how it used to whenever he threw parties in the past that day.

And what I never considered before losing one of my closest family members is the silence that comes with death. My dad’s front porch, which was often brimming with people on weekends in the spring and summer now feels like its own pocket of a ghost town.

My dad’s death brought to light for me how loud the quiet can be.

The blaring reggae music that he used to play at his frequent gatherings has been replaced with an eerie calm and one single tumbleweed that lets us know there shall be no real party without him there. Sometimes I feel like an old person recalling the good ole days, internally raving about the days of yesteryear, passionately flailing my arms as I try to convince people who weren’t there that it wasn’t always this way, no.

I swear there used to be music, and people, and fun!

I swear there used to be my dad.

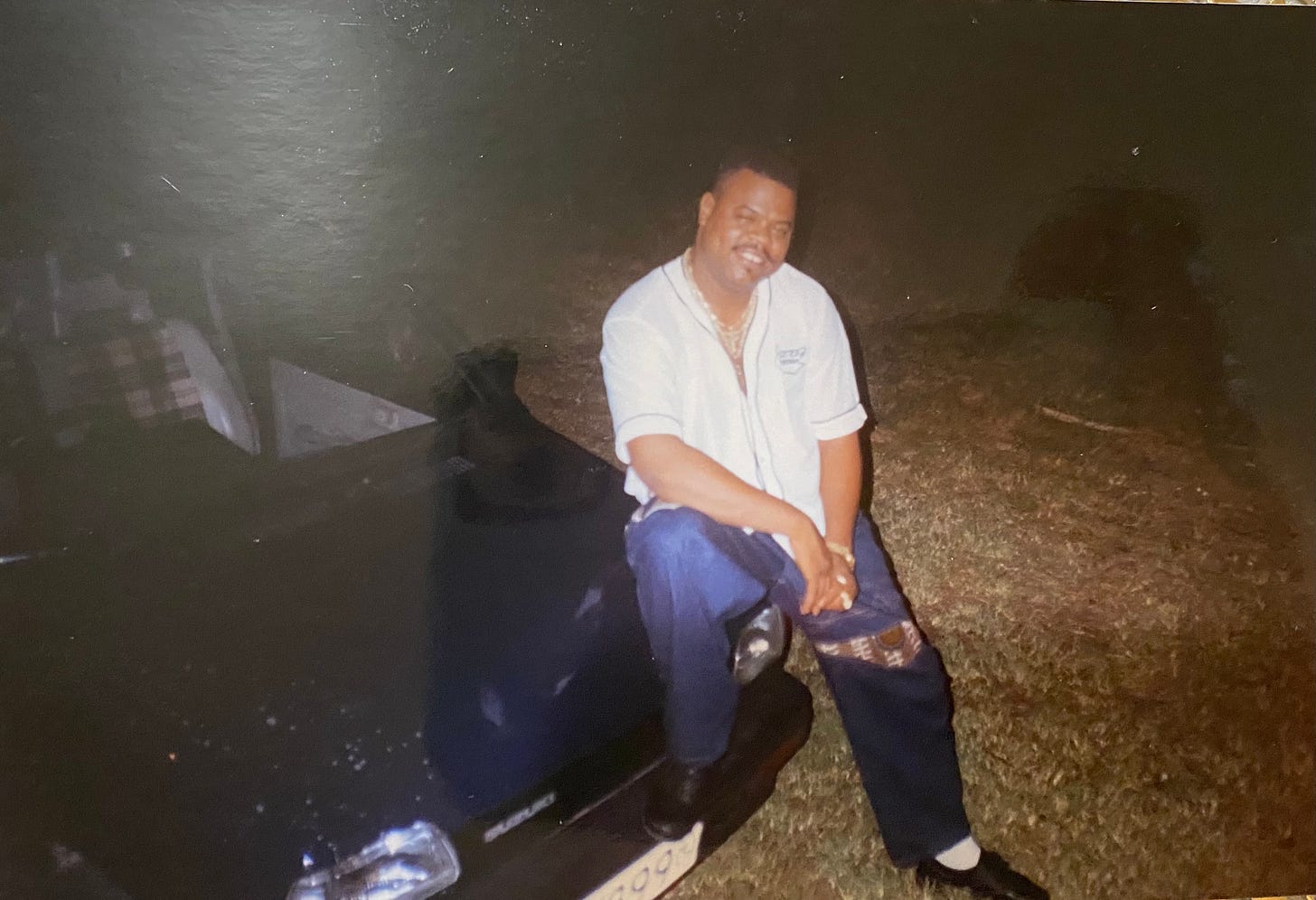

He was a social butterfly who landed on the shoulders of anyone willing to hold a conversation. A social butterfly who spent most of his life in flight, having been forced out of his cocoon prematurely due to orphanhood.

I both loved and resented my dad when he died and now, I love, miss, and am still kind of angry at a ghost—a memory whose only proof of existence is now word of mouth, physical photos/documents, and a gravesite.

I believe my dad was angry at ghosts for most of his life, too. When he was alive, he punched, screamed, and kicked at demons that only he could identify.

My dad’s explosive anger was a quick, piercing knife to the heart, and when it subsided, he acted as though the knife had never been there. You were to recover from his jabs just as quickly as he recovered from his fits of rage. When his sun was back out, he didn’t realize or care that he had left his loved ones with gaping wounds—blood converging with rainwater—behind him in storms of his own creation.

How I would have loved to share in his joy—however fleeting—more often, to sunbathe with him. I was too busy trying to recover, to dry off, to stop the bleeding.

I emerged from my father’s tornados a drenched and shaken cat—lucky that I had a good mother to go back home to. A sensitive and loving angel to nurse my psychological wounds. Like any animal, I eventually learned to seek shelter before the storms even came, which led to long periods of isolation from him in adulthood. When my father died, I hadn’t seen him in months, even though we didn’t live that far from each other. He always asked me when I was going to come over, not realizing or seeming to care that animals can get pretty banged up in stormy weather.

Up until his death, he never stopped knocking —and occasionally banging—on the barricade that I had slowly ejected between us over the years, still failing to understand (or care) why I always checked the weather before answering, if I answered at all.

When I think of the good things about my father, I’m thankful for his great big hugs and for all the times he managed to suppress his internal storms and show his love. He was affectionate and boisterous, and to him, I was beautiful, not merely because I was and am, but because he thought of himself as beautiful, and I was, after all, of him.

When we got moments alone without all his other kids, I sat in the passenger side of his cars and vans over the years. He would lovingly stare at me and ask: “How yuh suh pretty?”

When he missed me, and I him, he would say: “I long to see yuh pretty face.” I would reply, “I long to see yours, too.” That always amused him and he would chuckle as if this particular call and response hadn’t been a part of our interactions as father and daughter for nearly two decades.

My sister who is my sister in blood but not in spirit takes an unflattering photo of me on her Razr. I’m almost sure that I asked her repeatedly not to show anyone, not to show our father. Because children can be mean, and she was a particularly mean child, she showed our father anyway. He guffawed and asked, “Who is that?” He didn’t recognize me, his daughter, in the picture. He said something like, “I’m glad that’s not me!” And the day continued as normal, except I think I maybe snuck off somewhere to cry.

I knew that my dad didn’t think I was ugly. He called me pretty all the time and didn’t recognize me in the photo, after all. In that moment, though, I felt hideous.

Loss is intrusive and takes no prisoners. Loss is inconvenient and doesn’t give a shit what you’re doing when it comes knocking at your door.

Loss (especially sudden) is a random drop of blood on your yoga mat, like straight out of a horror movie. Loss is a bug in your green tea, a sharp pain in your side while you’re cooking breakfast.

Loss doesn’t care if you have a job, or if you graduated from college. If you’re famous, or if you’re doing yoga for your mental and physical health on what you thought would be a good, peaceful Sunday.

Loss reminds us that nothing matters but the people we love.

When death comes knocking, it’s not a pitter-patter, but a loud bang, a roundhouse kick, even, at your door.

My dad would have been a miserable bed-bound person, having been on the go his entire life. I think he would have been a problem patient had he been trapped in a hospital with no foreseeable departure. My father was a doer, a mover, a shaker, a driver, a dancer, a hugger, a kisser, a local socialite, a domino and volleyball player, a party thrower, a joker, a rager, and in the end, a lover of life, even though it seemed that that love often went unrequited.

I feel his restless spirit within me when I go to bed late and still awaken early. When I choose the 8:30 AM Zumba class over the 8:00 PM one whenever I can. When I lament the fact that my body needs rest/sleep to function because I just want to be up for all of it—whatever it is. When I try something new, I hear him in my head, telling me, “Do yuh ting, Mami!” or, “I know you can do it!”

When I went skydiving and sent him a video of it a couple of years back, he said, “Yuh have a lot of nerve! Yuh such a brave girl, Mami! Yuh brave like yuh Daddy!”

And he was brave. I am genuinely honored that he thought I was brave, too.

Loving and learning him both in life and in death means loving and learning myself. Grappling with my resentment with his physical form and with his ghosts means holding a mirror up to the parts of myself that I don’t like, and facing them—as scary as that is.

My father would demand kisses and hugs and refer to himself as my “Daddy” well into my twenties. In these moments, I was, in a sense, daddy’s little girl. As many children as he had, I felt he had a way of making each one feel special. I felt in these moments that he was always looking for himself in me and his other children—looking for himself in his constant creation of different versions of himself, perhaps because he wasn’t but 16 when he started losing his closest kin.

When someone stole my iPod in grade school, he showed up at my school bright and early one morning, demanding to speak to the principal. “I WANT TO TALK TO THE PRINCIPAL!” I had heard that he had announced, with a presence, voice, and stature that would make any proper white man shake in his penny loafers.

“I don’t like nobody bodda mi pickney!”, he had always said.

Weeks later, a glass window was ejected between the office staff and parents at my school. My family and I suspected we knew why.

These were the times when I felt protected and the sun was out. In these moments, I almost forgot that there were ever storms. In these moments, I let myself forget that the sun would ever set, or that our sky could one day fill with clouds again. These are some of my favorite and warmest memories of my father.

My father died how he lived: fast, unpredictably, and without anyone’s permission or input.

Following in the footsteps of his physical form, his ghost continues to knock and sometimes even slip through the cracks of my own personal Fort Knox. I don’t know if I’ll ever forgive him or his ghost for the rain, but I love him, and I can acknowledge that there was, indeed, some sun—more than one would expect from someone whose early life was so dreary.

Lately, when I peek out the tiny window of my bunker and I see hints of sunshine on the horizon, spot green vans, and hear a faint knock, I step outside and flood myself with all the good memories of my father.

And with those, I create an endless summer in my mind.

whoa, this was so beautiful and let me come along for you and your dad's journey. i was teary eyed when he started singing nobody's child and from there, they never really stopped coming.

so many parts of this story really landed with me and resonated as a fellow member of the dead dads club. seeing reflection like this remind me of how complex grief is and i feel like your telling really spoke to this. thank you! sending you lots of love and whatever else you need

Thank you for share your deep thoughts.

From one Jamaican to another, who also shares your birthday month with you and your dad.

04/23/70🤍🇯🇲